He can’t hear well, they told us. But, he can definitely hear.

Beautiful things

It wasn’t what I expected. I expected more color, more toys, more sunshine. I don’t know. Afterall, it wasn’t a state orphanage. Maybe I expected it to look more like some Chinese version of the daycare center where I worked for a summer in college. It didn’t.

The doorman muttered all sorts of things to us that even our translator had trouble understanding. But, he waved us through and smiled when he saw the director walk out to us. He asked us if we slept well. We assured him we did, and he said he was surprised because he thought we might be too excited to sleep.

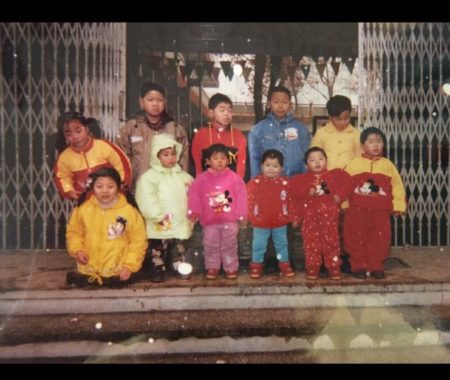

The front hall was clean. dark and cool. damp. Some signs seemingly about rules for safety with interesting clipart were posted making that front hall look not unlike that of an office building, one no one really used. Two children’s areas were on that hall, each having two rooms, one for beds and one for play. We were invited right into the first area, like a friend might invite us into her living room. Come in. See what we’ve done with the place. When you admire it, I’ll smile and tell you to stop, but it will make me feel really good. In our aprons that looked like children’s hospital gowns and paper shoe covers, we joined the staff in the playroom.

There was nothing spectacular about the space. It wasn’t bad. I’ve said spaces with much less. But, it wasn’t what I thought it would be. With chalky paint, uneven and worn out floors, worn out lots of things, it really wasn’t all that beautiful. But, we stayed. Of course we did. This is where we had been asked to go. This is who wanted “expert” training on early childhood education and class management, about caring for children assigned the umbrella diagnosis of cerebral palsy, and about discipline and correction. We didn’t just stay; we watched.

It was nearly evening but the room got a little brighter as we watched. Brighter still was that place after we spent time in both rooms. The rooms looked different when we left that first day. In fact, even the doorman may have looked a little different.

It wasn’t like that daycare center with a play kitchen, dress up corner, and reading nook. It wasn’t like the state orphanages where I’ve served either. It was different. And, there were beautiful things there that weren’t at all worn out. Beautiful things that had nothing to do with donations from foreigners or painted murals on the wall. It just took a little time to notice them.

Two full days of trainings would start the next morning, trainings that would give us the opportunity to teach a few things and tell them how we love what they’ve done with the place.

I might have been too excited to sleep that night.

the beautiful girl who is my friend

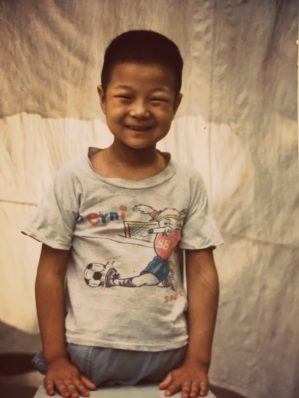

She was hard to notice. Without legs, she held onto small wooden handles someone likely had made just for her to get around. While her stature was the same as the children around her, I could tell she wasn’t one.

I was hard not to notice too as a foreigner in a group of foreigners who had come to volunteer and who weren’t just coming to admire little babies in the nursery rooms. I’m sure she saw me, but she avoided eye contact. I remember putting a handmade scarf around her neck at the end of that visit and touching her cheek and telling her she was beautiful. She couldn’t understand my words; I think she understood me because next time I came, she looked at me and tried to talk to me. On that trip, I learned a bit more about her. She had been there since she was a newborn. Someone named her MeiNu, beautiful girl. As others who came during the same season were adopted or eventually grew up and ventured out to school or to try to find jobs, she remained.

She was a kindergarten teacher now, a good one. I know because I got to sit in her class and watch her teach. The whole scene pretty much amazed me. A girl who was an orphan and had never left the orphanage now taught other orphans with patience and tenderness.

On the next trip, I found myself again in her classroom, sent there to observe a few children and make some suggestions. Instead, MeiNu was who I wanted to observe more. The video that I captured that morning of her as she came alongside a little boy who was not able to help him become able became the highlight of the training I offered there that year as well as the next. [read my narrative about it HERE.]

She and I became friends sometime after that. She was no longer the girl with no legs who was an orphan turned teacher. She is MeiNu, beautiful girl, who likes makeup and selfies and silly phone filters. She wants to learn English, dreams about going to America one day, and wants to marry (but not just anyone, the person she can love and who loves her, she explained to me). She’s also one of the bravest people I know. This past summer, she quit her job as a teacher in the orphanage and took all the money she had saved and took a train to Shanghai. By. her. self. She got a job as a “course consultant” which she says she doesn’t like and is boring. But, she’s living on her own, using a wheelchair and taking taxis and going out to restaurants just like any other 28 year old woman.

When I told her I was going to be in the same city she was, she insisted we meet up. She took the day off of work to come see me and my companions, gave me a necklace and gave snacks to all four of us, and took us all out to the fanciest hot pot dinner I’ve ever gone to in China (complete with required hair bands, aprons, and baggies for our phones). We didn’t say much to each other since her English isn’t good and my Chinese is worse. But, we were together not as a foreigner observing her or judging her, just as friends.

A mystery I’m glad to accept

It was nearly a year ago when I first met her. She was one of the smallest babies there. While she wasn’t demanding, she captivated our attention. She had big round cheeks and kicked her feet when we spoke to her. But, we knew something was wrong. She was yellow. Everything about her was yellow. And, when we held her, the ayis pointed it out. They’d point to their own cheeks and then shake their heads, point to their own eyes and frown.

Her liver was broken. That’s what they told me. While I don’t know anything about that, I knew it was serious. She needs a new one to live, they told me, and she won’t get one. The ayis in her room seemed to accept it. I guess they learn to accept a lot of things. They have to. They can only do the job they are told to do. They care for babies—until they are placed in a foster home, until they are adopted, until they get too big and move to another room and into a coworker’s care, or until they die. That’s what they do everyday. They don’t make decisions or set policy or change systems. For this baby with chubby cheeks and fiesty kicks, they assumed they’d feed her and change her and hold her until one day, her body would all be broken and she would die.

I talked to the ones who do make decisions. Can something be done? Can she be transferred somewhere else? What if money could be provided for the surgery she needs? No. No. No. They weren’t mean about it. I could hear the regret through the language foreign to me and the way they shook their heads and sighed. They wished they could do more, but it was impossible. Even if there was a place that would take her, even if there was money to pay for it, there was no liver to give her. No one in China would donate their child’s liver to save an orphan baby.

When we left that place, I rubbed her back and touched her head. And, I accepted it too. The world is a broken place, and she’s a living example of the brokenness.

It was months later when I received a photo via WeChat. Despite the tubes and tape, I knew it was her. It made no sense, but I knew it was her.

Few words were shared. Only that she had traveled all the way to Shanghai, that she had received a new liver, and that she was in intensive care but would recover. How the decision was made, how it was arranged, how it was paid for, how her life was spared, I have no idea. Somehow, the impossible was made possible.

About a month later, another picture arrived. This time words came with it: Vitals are normal. Yesterday afternoon, was transferred to the general ward.

Two weeks later, a new picture arrived, this time with the words: She was discharged. It was taken on the same day.

She hasn’t returned to the orphanage yet. She’s in a home for babies recovering from surgeries. There she’s monitored for any signs of rejection, and she goes to the hospital once a week for more detailed examination. She’s well cared for and getting what she needs.

When we go to China, we fly into Beijing. But, this time, we took a little detour.

We will never know how it happened, but we can testify that it did happen. Somehow the decision makers moved from acceptance to discontentment and to action to share her need for a new life. Somewhere a child died and that child’s parents decided to give life to a child who had no future, no hope. Somehow she traveled 900 miles to receive that new life through a surgery that someone unknown paid for.

I am one who asks a lot of questions and works hard to get answers. I want to know all the hows and whys to things. But, not today. Even if I could ask all the questions I have, I do not think there are answers that could fully explain her story. How it all happened, I don’t know. One thing I do know, she was dying, and now she will live. That’s a mystery I’m glad to accept.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- …

- 371

- Next Page »